Today we discussed a new way to combine two groups: the Free Product, and looked at the Cayley Graph of such products which led us to discuss Bass-Serre Trees.

The Free Product of Groups

Definition. Let ![]() and

and ![]() be groups. The free product

be groups. The free product ![]() is the group whose underlying set is

is the group whose underlying set is

![]()

With the operation of concatenation along with free reduction and “glomming” of elements of the same starting group.

Essentially, we are alternating elements of ![]() with elements of

with elements of ![]() , allowing for the possibility of starting with either an

, allowing for the possibility of starting with either an ![]() or a

or a ![]() and ending with either an

and ending with either an ![]() or a

or a ![]() . This definition looks very similar to the definition of the free group on two elements. One key difference, however, is the lack of exponents on the letters in the words (in the definition). This arises from the fact that in

. This definition looks very similar to the definition of the free group on two elements. One key difference, however, is the lack of exponents on the letters in the words (in the definition). This arises from the fact that in ![]() , we are creating words on a generating set and in

, we are creating words on a generating set and in ![]() we are creating words on the entire underlying set.

we are creating words on the entire underlying set.

Like free groups, our group operation is concatenation, but with a small twist. Our underlying set is not actually the words themselves, but the equivalence classes represented by the words. This ensures that we continue to stay within the group after concatenation. We also continue to allow for free reduction, similar to free groups. Finally, we don’t want two elements of the same group right next to each other. Instead, we determine the value of their product within the group and use that element instead. This allows us to continue following the notation set out above.

Let us now consider what the presentation of ![]() looks like. Let

looks like. Let ![]() and

and ![]() . Then,

. Then,

![]() .

.

The ![]() symbol represents the disjoint union of

symbol represents the disjoint union of ![]() and

and ![]() . This means that we have to name the elements of

. This means that we have to name the elements of ![]() and

and ![]() such that they share no elements in common. The relators are the words that are equivalent to the identity under the group operation. These don’t change when we add more generators, so the relators of

such that they share no elements in common. The relators are the words that are equivalent to the identity under the group operation. These don’t change when we add more generators, so the relators of ![]() are simply all of the relators of

are simply all of the relators of ![]() and all of the relators of

and all of the relators of ![]() . One might ask, are there any relators which combine both elements of

. One might ask, are there any relators which combine both elements of ![]() and elements of

and elements of ![]() ? The answer is no, we do not allow any relators which we do not already have and since we have a disjoint union of the elements, no relators combine elements of

? The answer is no, we do not allow any relators which we do not already have and since we have a disjoint union of the elements, no relators combine elements of ![]() with elements of

with elements of ![]() .

.

Since we can have words of any length and there is no mechanism for a word containing ![]() ’s and

’s and ![]() ’s to be the identity unless it is trivial, it naturally follows that

’s to be the identity unless it is trivial, it naturally follows that ![]() is infinite unless at least one of

is infinite unless at least one of ![]() and

and ![]() is trivial and the other one is finite. For example, if we take

is trivial and the other one is finite. For example, if we take ![]() we get

we get ![]() , which is

, which is ![]() , or the infinite reflection group. Even though

, or the infinite reflection group. Even though ![]() is about as finite as we can get, and we are starring it with itself, we still get an infinite group.

is about as finite as we can get, and we are starring it with itself, we still get an infinite group.

Another example of free products if ![]() . More generally,

. More generally, ![]() since we just combine the two lists of generators and continue to have no relators.

since we just combine the two lists of generators and continue to have no relators.

Cayley Graphs of Free Products

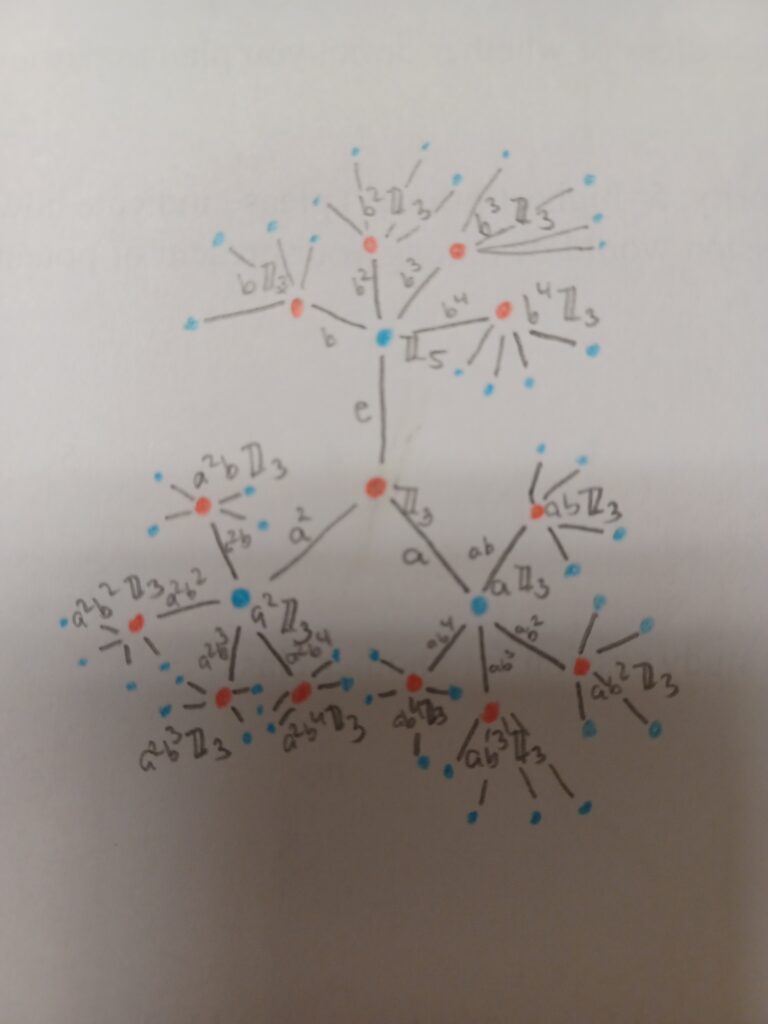

Let us now consider the Cayley graph generated by one of these free products. Consider ![]() . The Cayley Graph is shown below.

. The Cayley Graph is shown below.

This Cayley graph alternates triangles (three-cycles) with undirected edges representing the ![]() and

and ![]() nature of the group, respectively. Similarly, for

nature of the group, respectively. Similarly, for ![]() we get:

we get:

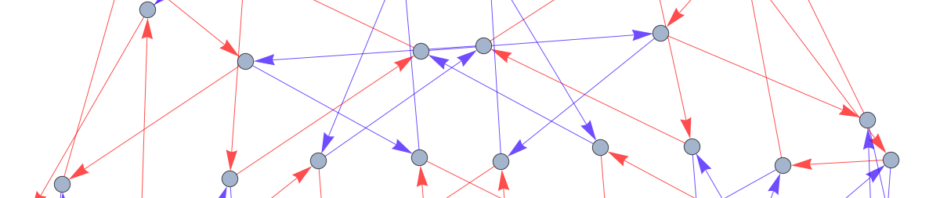

This graph consists of alternating triangles and pentagons. If we squint, close one eye, and spin around, this graph kind of looks like a tree. In fact, we can build a tree out of it called the Bass-Serre Tree (see below).

To construct the Bass-Serre Tree we place vertices on the inside of each of the triangles and pentagons and connect them through the vertices of the original Cayley graph. We label the new vertices with cosets of our two original groups and the new edges with the vertices they passed through.

Final Facts and Theorems

Finally, we stated and, in some cases, proved two statements about biregular trees and free products.

Theorem. ![]() acts on a biregular tree such that the fundamental domain of the action is two vertices with a single edge connecting them where the stabilizers of the vertices are conjugates of factor groups and stabilizers of edges are trivial.

acts on a biregular tree such that the fundamental domain of the action is two vertices with a single edge connecting them where the stabilizers of the vertices are conjugates of factor groups and stabilizers of edges are trivial.

Corollary. If G acts on a biregular tree such that there exist subgroups of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , so that the fundamental domain of the action is two vertices with a single edge connecting them where the stabilizers of the vertices are conjugates of factor groups and stabilizers of edges are trivial, then

, so that the fundamental domain of the action is two vertices with a single edge connecting them where the stabilizers of the vertices are conjugates of factor groups and stabilizers of edges are trivial, then ![]()

We also briefly discussed the free product with amalgamation, but due to space and time limitations and I will not go into that here.

Lastly, we defined virtually and introduced a theorem that we will prove next time:

Definition. A group ![]() is virtually P if there exists a finite index subgroup

is virtually P if there exists a finite index subgroup ![]() such that

such that ![]() has the property P.

has the property P.

Theorem. If ![]() and

and ![]() are finite, then

are finite, then ![]() is virtually free.

is virtually free.

Resources Used:

Free product of groups. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Free_product_of_groups&oldid=46986

Free Product. Wikipedia. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_product

Nice post Michaela! I was curious about Bass – Serre trees and did a wikipedia search and came up with this

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bass%E2%80%93Serre_theory

There are a lot of rich connections with fundamental groups!

Your post helps me understand Bass–Serre trees a lot better! For me, I understand the construction of Bass–Serre trees as utilizing the rigidity of possible symmetries of by grouping things together. Again, we look at the example

by grouping things together. Again, we look at the example  and

and  . Here, we cannot move a triangle to three vertices of a rectangle. Therefore, we group things together as a tree so that the symmetries can be more easily expressed.

. Here, we cannot move a triangle to three vertices of a rectangle. Therefore, we group things together as a tree so that the symmetries can be more easily expressed.

It was a nice idea to use as one of the factor groups in your free product example because it makes the diagram nice and clean. My only question about the post is why you don’t also take the disjoint union of the relators if you are taking the disjoint union of the generators in your definition of the free product? Maybe I’m just not super comfortable with the formalism of a disjoint union.

as one of the factor groups in your free product example because it makes the diagram nice and clean. My only question about the post is why you don’t also take the disjoint union of the relators if you are taking the disjoint union of the generators in your definition of the free product? Maybe I’m just not super comfortable with the formalism of a disjoint union.

Since the generators are seen as distinct, that implies that the relators from each group are distinct – since group A contributes relators that are words on and

and  contributes relators that are words on

contributes relators that are words on  , if

, if  and

and  have no overlap then the relators from

have no overlap then the relators from  and from

and from  can’t have any overlap either.

can’t have any overlap either.

A delightful post! Bass-Serre trees are very pretty; all the dangling factor groups make me think of real trees. Free products helped me understand free groups better! For , at every letter, you can play around however you want within the confines of your group; whatever you end up outputting, you have to move on to the other group and repeat the process, and so you end up embedding the Cayley graph of each group constantly into the Cayley graph of the free product. This helps explain why you’re able to squint, as you say, and find a tree: every vertex of

, at every letter, you can play around however you want within the confines of your group; whatever you end up outputting, you have to move on to the other group and repeat the process, and so you end up embedding the Cayley graph of each group constantly into the Cayley graph of the free product. This helps explain why you’re able to squint, as you say, and find a tree: every vertex of  points toward the entirety of

points toward the entirety of  and vice-versa, so each factor group should be a unique jumping point to the other factor group, and that uniqueness gives rise to a tree structure.

and vice-versa, so each factor group should be a unique jumping point to the other factor group, and that uniqueness gives rise to a tree structure.